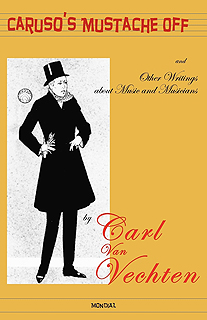

Carl Van Vechten:

Caruso's Mustache Off

and Other Writings about Music and Musicians

Selected, edited and with a Preface by Bruce Kellner

366 pages.

1. Book version: ISBN 9781595690708 or PayPal. 5.5 x 8.5 in (21,5 cm x 14 cm)

2. eBook version: Google Play / Kindle

From the preface by Bruce Kellner

Carl Van Vechten’s (1880–1964) career included some perspicacious criticism at a time when somnolent audiences in America were paying little attention to the twentieth century and laboring to hang on to the nineteenth. Van Vechten’s early training in musical theory and as a pianist—he performed in public recitals on more than one occasion while he was attending the University of Chicago at the turn of the twentieth century—proved valuable. Also at that time, he became smitten with ragtime and early jazz through Chicago’s black stage shows and saloons...

During that early period in his career—in addition to his regular reviews of musical performances around the city—Van Vechten began holding extensive “Monday Interviews” with musicians and opera singers, a series of richly informative question and answer sessions, masquerading as genial conversations. The reigning divas and primo dons at that time were the popular equivalent of current rock and rap performers on stage, or fi lm and television stars with large followings of celebrity hunters who cling with equal vigor to accounts of private lives and public appearances. Later, these interviews served Van Vechten well for a book of biographical portraits of musicians, Interpreters and Interpretations (1917, revised as Interpreters, 1920, reprinted 1977).

He was on the staff of the New York Times for nearly seven years, including the 1908-1909 season during which he served as Paris correspondent. He resigned in 1913 to become drama critic for the New York Press. After that paper folded a year later, he served as editor of two literary journals, Trend and Rogue, and then began publishing annual volumes of musical criticism in the form of personal essays that were always luminously well-informed because of what he had nurtured into an encyclopedic musical background, historically solid, laced with ample anecdote, and even fun to read: Music After the Great War (1915), Music and Bad Manners (1916), Interpreters and Interpretations (1917), The Music of Spain(1918), The Merry-Go-Round (1918), and In the Garret (1919). Then, after producing a mammoth book about cats, The Tiger in the House (1920, never since out of print), he turned to fiction, publishing seven novels in hasty sequence: Peter Whiffle: His Life and Works (1922), The Blind Bow-Boy (1923), and Nigger Heaven (1926) were bestsellers, the latter informed by his long-standing fascination with African American music and theater. The Tattooed Countess (1924), Firecrackers (1925), Spider Boy (1928), and Parties (1930) all sold well. On the strength of their success, Van Vechten revised a number of essays from his earlier books for Red, devoted to musical subjects (1925), and Excavations, devoted to literary and biographical subjects (1926)...

His pioneering essays about African American blues, jazz, and spirituals from the mid-Twenties, written at a time when white auditors still paid little if any attention to black music, are astonishingly perceptive, having had their genesis at the turn of the century for Van Vechten when he fi rst began to champion black performers and music in Chicago and New York in his early newspaper work. These too, have provided ample material for a posthumous collection, which I edited as “Keep A-Inchin’ Along”: Selected Writings about Black Arts and Letters (1979).

Before Carl Van Vechten's later careers--as the first dance critic in America, as a best-selling novelist during the Jazz Age of the Twenties, as the leading white champion of African American arts and letters, and as a celebrity photographer--he was Assistant Music Critic for the New York Times (1906-13). Subsequently, he wrote seven volumes of lively and often audacious essays on musical subjects.

He was first to offer serious assessments of the music of Igor Stravinsky, Erik Satie, George Gershwin, and the operas of Richard Stauss. He wrote the earliest study in America of the music of Spain. He was first to advocate musical scores for movies. He contended that ragtime and jazz were the only uniquely American music, at a time when they were dismissed or ignored by other critics.

This collection gathers a broad sampling of Carl Van Vechten's work long out of print and heretofore uncollected, including Red, his own revisions of his writings about music that he wished to preserve. They have been edited with an introduction by Bruce Kellner, Successor Trustee for the Estate of Carl Van Vechten.